Using Katas To Improve

Some Background Thoughts

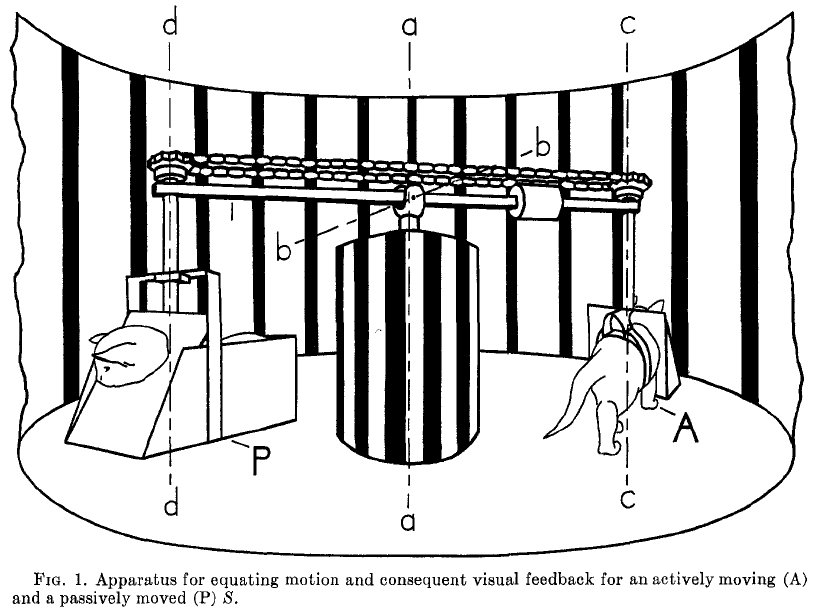

There is an experiment from Richard Held and Alan Hein who raised kittens in total darkness. For a short period during the day, the kittens were placed in a carousel apparatus where the lights were turned on. One basket allowed the kitten to see and interact with its environment (the active kitten). The other had a hole for the head so the kitten (the passive kitten) can have the same visual experience but without the interaction.

At the end of the experiment, the passive kitten was functionally blind whereas the active kitten was normal.

This idea has stuck with me. The idea that you need to interact with your environment. You are functionally blind when you only have book knowledge. I need to code (and code a lot) to really get that knowledge at the instinctive level.

It is also important to do things quickly to develop fluency. Fluency allows you the freedom from the mechanics of what you are doing so you can focus on the main ideas.

First Kata Experiment

When I joined 8th Light, I came across katas. The idea of a kata is to practice coding by doing it repetitively. You build muscle memory in the mechanics of coding – setting up the editor, reacting to errors, letting your fingers get used to the controls. Initially I thought it was an amusing little activity. Then I started to wonder if I can do a kata on something more than coin-changer or roman numerals, something with a little more substance. I thought it could be possible to write tic-tac-toe as a kata. My main goal is to develop a workflow so I can write it under an hour. I also wanted to record myself and bought Screenflow. After all, the kata is meant to be a performance.

I did my first tic-tac-toe kata in ruby, a language I know well. I used RSpec has my testing framework, something I was less familiar with.

In the beginning I spent a lot of time setting up my testing environment and researching the web when I got stuck. For example, I forgot to add an “it” block in RSpec. It generated an error message I couldn’t understand. I worked around it by making the test pass. I didn’t figure it out until the next day when a co-worker (Meagan) pointed it out after she saw the video of my kata.

I saw myself steadily improve in my next version of the kata. I made 6 attempts before I was finally able to do it in less than an hour. I was able to interpret error messages better. I was able to set up my testing environment faster. I improved my code by finding more elegant ways to solve a problem. For instance, if I wanted to separate a list into groups of 3, I would write:

lst.group_by.with_index {|e,i| i/3}.valuesAfter having writing it several times, I thought there’s probably a better way. I finally came up with:

lst.each_slice(3).to_aI don’t know if I would have revisited this problem if it weren’t for the kata.

I also saw the effect when I forgot to add a test. This brings another important point. I saw probably every type of error/bug because each time I do a kata, I make different mistakes. You get a richer experience from it. You’re able to focus on the source of the error/bug rather than wonder about the correctness of your code, after all, your code is similar to your previous versions so you know it should have worked. You can always use diff to compare your versions if you get completely stuck.

Since the kata is repetitive, it allows you to reflect on how you use your editor. You wonder if there is a better way to get from one point to another. You can test out new keystrokes and see if it makes a difference.

In the end, I would say the kata has vastly improved my workflow.

Using Kata To Learn A New Language

I tried another experiment. What would it be like to use a kata to learn a new language? Would I be able to do get it done under an hour? I tried it out with Haskell.

I’ve heard people mention Haskell so I wanted to give it a go. The first step was to find a resource to read up on it. I read through Learn You A Haskell. After a few days, I was ready to start coding. Just like the passive kitten, I was functionally blind. I knew about Haskell, but I couldn’t code it. I needed to interact with the language. What better way than to do a kata?

I already had a set of routines I wanted to code and I knew the algorithm. The only thing standing in my way was the language and the kata gives me a controlled environment so I can focus on it. It also gave me a good way to reflect on the problems I encountered. Since your errors are recorded, I didn’t have to remember things I need to look into or remember what error messages lead me to a particular fix. It’s like having superhuman memory.

After I got the setup for testing out of the way (using HSpec), syntax became my main problem. Every time I wrote something, I would get parse errors. I would backtrack to a simpler form until I got it to work. After about an hour, I was only able to write a constructor. I also had to set up guard (for automatic testing), which took up a good chunk of time. I kept my recordings to about an hour for the rest of my katas whether I finished or not.

When I reviewed the video of my first kata, I saw long pauses where I was thinking about a particular issue. Then I saw myself researching and eventually solving the problem. The video reinforced everything I had learned. I didn’t have to take notes or remember how the problem originated. It was all recorded for me. This allowed me the freedom to try new techniques and go beyond my comfort zone. I can always review it and see where things went wrong.

When you learn a new language, you have a feeling that you know enough to do small things but you have the uneasy feeling that your knowledge is tenuous, that it can slip away from you if you’re not paying attention. That feeling started to evaporate on the second kata. I developed idioms so I can do things automatically. That gave me a base to build on. By the third kata, the video showed a steep increase in my performance. I was no longer hesitating and going off to Google. I was still making a lot of errors, but they were different errors. The ones I had encountered before were quickly dismissed since I’ve already solved it in the past.

Since I was new to the language, I was not able to complete the program in the early katas. It did give me a good research points when I finished recording. I knew at least that I can get to the same point as the previous kata. I needed just a little bit more knowledge to go further. It is very encouraging when you can see yourself actually improve over each version.

It took me 10 tries before I was able to get a complete working version of my code. I was able to do it just a little over my hour target. I sped up the time on my Screenflow so it played for a bit over 16 minutes. When I tried uploading it to YouTube, it got rejected because they had a limit of 15 minutes. I knew I had to shave off 20 minutes so my video can run in 14 minutes. I was already typing as fast as I could. Then I realized that I could use the abbreviate command in vim. I made it so when I type “p”, it will type out “position” and that will save me keystrokes. I would add these abbreviations as I went along. I spent my off-kata time looking into shortcuts in vim.

I did some unrecorded katas to test out some new key bindings and some config changes for vim. My 13th kata was the charm. I was able to finish in a little under 50 minutes, which gave my time-compressed video to 14 minutes. I uploaded it to YouTube and was approved finally.

I encourage everyone to try using katas to improve their workflow. You’ll be amazed at what you can get accomplished.